Lesson Plan

TEACHING RESOURCES

First Steps

Guidelines to work with Indigenous Stories

Since Indigenous peoples and their way of life have been exoticized, marginalized, and

colonized in the Western realm of knowledge systems, it is pertinent for teachers to

understand how to work with Indigenous stories. Including Indigenous stories to teach a colonizer’s language in a responsible and respectful manner is challenging. Jo-ann Archibald’s (2008) book Indigenous Storywork and Parent and Kerr’s (2020) document “Indigenous Storywork Give Away for Educators” have been invaluable guides in my journey as a non-Indigenous, racialized educator in creating this curriculum. I draw on the teachings of ‘Storywork’ guided by respect, reverence, responsibility, reciprocity, holism, interrelatedness, and synergy (Archibald, 2008).

As teachers read the stories, they are encouraged to connect the narratives and cultural

teachings to their roots in the land. Archibald (2008) emphasizes the importance of patience and trust to listen to stories. The act of listening to stories goes beyond merely hearing the words, the stories should be told in a way that listeners should be able to visualize the characters and the actions. As the Elders say, it is important to listen with “three ears: two on the sides of our head and the one that is in our heart ” (Archibald, 2008, p. 8). Essentially, we engage with Indigenous stories in a synergy - the teacher as the storyteller, the students as our active listener, and the story itself that offers important teachings.

In many Indigenous communities in Canada, the storytellers are trained from childhood,

which can be daunting for educators who do not consider themselves skilled storytellers. A gifted storyteller has the ability to help their listeners visualize the story and its characters, making the narrator seem like part of the story. Lorna Mathias, a Nisga First Nations educator, observed during her graduate studies that her students noted several key traits of good storytellers: changes in intonation, expressive voice, physical actions, and most pertinently if the storyteller themselves display enthusiasm about the story ( Archibald, 2008, p. 132).

Ellen White, an elder and a gifted storyteller from the Stó꞉lō Nation of British Colombia recommends that teachers should first understand the story using visualization methods. For instance, drawing parts of story or storyboarding. She also recommends to read a page at a time, to read between the lines, recognize the levels of meanings embedded in the story, and immerse in the story to truly understand and value the story itself. This process would help in becoming a good storyteller (Archibald, 2008).

The act of telling or teaching through an Indigenous story requires a cultural framing and an understanding of the Indigenous community. Teachers are encouraged to research the communities mentioned in the units and prioritize reading texts written by the community itself rather than by outsiders. Archibald(2019) recommends that teachers use storybooks written by Indigenous people and learn to read and tell the stories that way. Once familiar with the stories, teachers can move to telling them without the book, but it is crucial to share the context and acknowledge the source of the story. There are cultural protocols or guidelines for working with Indigenous stories. As Archibald (2019) explains, there is a difference between traditional cultural stories and personal lived experience stories, with the latter being outside the purview of using them as teaching stories in a public forum.

For non-Indigenous teachers like us, it is crucial to culturally sensitize ourselves to the process of incorporating Indigenous stories in our curriculum. Providing context by showing pictures of the authors/storytellers, and the nations they come from will help learners connect with the people and places from where the stories originated. It is also important to remind students that many versions of oral narratives coexist, each told differently by various storytellers for diverse audiences. Unlike Euro-Western stories which are often written for children, Indigenous stories contain important teachings embedded within them, meant not just for children but also adults. Indigenous stories also do not follow the typical Euro-Western structure of having a tidy beginning, middle, and end. Instead, they often end in a moment of reflection, encouraging listeners to engage personally with the story and ponder on how the story might have ended. The meanings are often open-ended. The stories chosen for this curriculum unit reflect values for living in harmony with the territory and the land.

References:

- Archibald, J. (2008). Indigenous storywor : educating the heart, mind, body, and spirit .UBC Press.

- Archibald, J. (2019, August, 14). For educators. Indigenous Storywork. https://indigenousstorywork.com/1-for-educators/

- Parent, A. & Kerr, J.(2020) Indigenous Storywork Give Away for Educators. Indigenous Storywork.com. https://indigenousstorywork.com/resources/

Pedagogical Rationale

Stories are common to every culture, however they hold different meanings in different cultural contexts. As adults we tend to forget the stories that we heard as children from our grandparents or parents. Gray (2012) addresses the issue of how cultural materials are now used as forms of mass entertainment through the rise of cinema and television. Consequently, it has become more common for us to watch movies and listen to podcasts in our fast-paced technological world. Through the oral narratives, it is my attempt to reacquaint learners with the oral tradition of storytelling.

The lessons are designed on the principle of holism, representing the interconnectedness

between the spiritual, intellectual, emotional, and the physical world that forms a whole person (Archibald, 2008). The image of a circle, used by many First Nations communities in different ways symbolizes “wholeness, completeness, and ultimately wellness,” (p.11) involving the individual with the family, the community and the nation. This is framed in the understanding that we are responsible for our future generations and our ancestors, extending beyond human relations to include more-than-human beings — animals, birds, flowers, trees, rocks, land and other beings. The goal of these lessons is to raise the ecological consciousness by using language that is more nature-centric and critically examine the anthropocentric ways of viewing nature.

The lessons are designed organically, so grammar does not dictate their structure. Students are encouraged to engage in dialogue and reflective thinking that generates language. Teachers can choose to explain a grammatical structure at the end of the lesson based on the language generated by the students, teaching grammar organically. Alternatively, the teacher can explain the grammatical structure the next day, allowing time to prepare and recap the previous day’s learning. This approach provides an alternative to the structuralist and competency-based framework of teaching a language (Canagarajah, 2020).

The units are organized to present alternative ways of viewing the natural world, challenging the current utilitarian perspective that sees nature as a resource. Although the focus of the lessons is on skills development, especially listening, reading and speaking, the purpose of these lessons goes beyond skills development to address the spiritual and emotional dimensions of learning from the land. Many of the activities are inspired by the concept of visual metaphors, encouraging learners to engage with the content spiritually and emotionally (St. Clair, 2000).

The lessons also do not suggest time-bound activities. Unlike Western understandings of time, in the Indigenous worldview

“things happen when they are ready to happen"...time is not “structured into compartments.…

The solution is to allow for flexibility and openness in terms of time within practical limits”

Dr. Gregory Cajete (1986)

References

- Archibald, J. (2019, August, 14). For educators. Indigenous Storywork. https://indigenousstorywork.com/1-for-educators/

- Cajete, G.A. (1986). Science: a Native American perspective: A culturally based science

education curriculum. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, International College, Los Angeles.

- Gray, J. (2012). Neoliberalism, celebrity and ‘aspirational content’ in English language teaching textbooks for the global market. In D. Block., J. Gray., & M. Holborow. Neoliberalism and

Applied Linguistics. Taylor & Francis Group.

- St. Clair, R. N. (2000). Visual Metaphor, Cultural Knowledge, and the New Rhetoric. ERIC.

education curriculum. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, International College, Los Angeles.

Applied Linguistics. Taylor & Francis Group.

Lesson Plans

UNIT 1 - Creation Stories

Rationale

In ELT, metaphors are often understood as a literary device that enhances the quality of one’s writing. However, metaphors are ways in which we understand life. It is hidden in the words we use. Lakoff & Johnson (2003) tell us that “metaphor is pervasive in everyday life, not just in language but in thought and action (p.3). The authors state a simple example showing how certain concepts govern how we view the world and relate to people. The cultural values of consumerism for example come from expressions like “more is better,” “bigger is better” (p.22). Hence, the accumulation of wealth and goods becomes embedded in cultures driven by the English language.

The creation stories in this unit chosen from the Indigenous nations of Canada will introduce students to the language of ecology. The lessons also act as a way of introducing the metaphorical nature of Indigenous stories that are grounded in specific cultural values. The sources of Indigenous knowledge are the land, the spiritual beliefs and ceremonies, the traditional teachings often embedded in the stories (Archibald, 2008). In this lesson, Ss will be introduced to the phrase “All my Relations.”

Thomas King, Cherokee storyteller explains,

All my relations is a first a reminder of who we are and of our relationship with both our family and our relatives. It also reminds us of the extended relationship we share with all human beings. But the relationships that Native people see go further, the web of kinship extending to the animals, to the birds, to the fish, to the plants, to all the animate and inanimate forms that can be seen or imagined. More than that, “all my relations” is an encouragement for us to accept the responsibilities we have within this universal family by living our lives in a harmonious and moral manner ( as quoted in Archibald, 2008, p. 42).

Level: Upper intermediate

Number of students: 15

Total duration: 90 mins + 90 mins

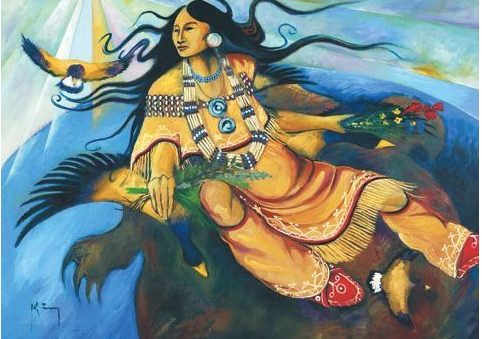

#1 “Skywoman Falling” - A creation story adapted from the oral tradition, and Shenandoah and George,1988 published in the book Braiding Sweetgrass by Dr Robin Wall Kimmerer.

# 2“Creation Story” - Told by Grand Chief William Charlie from the Sts’ailes Nation, British Colombia, Canada.

Objectives:

-

By the end of the lesson, Ss understand the values of community, relationality, generosity and sacrifice.

-

Be able to reflect on the nature of reciprocity and responsibility between humans and the Earth.

-

Be able to identify ecological metaphors.

-

Be able to narrate a story in their own words.

Before beginning the Teacher (T) should sensitize Ss about Indigenous communities.

T could start the discussion by eliciting if they know the word “Indigenous”. What do they understand by it. Do they know of any Indigenous communities from their country?

Lesson 1 - Skywoman Falling

| Lesson Stages | Objective | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Lead in | To understand the meaning of creation stories and remember creation stories from the students own culture. | T to Ss -

|

| Listening | To activate memory and listening skills. | Classroom seating - Circles - This is adopted from the First Nations Pedagogy(2009) of the Talking Circle. [firstnationspedagogy.ca/circletalks.html](http://firstnationspedagogy.ca/circletalks .html) Ts are encouraged to read the website. The idea is to encourage Ss to be engaged with their hearts and minds as they listen to the story. T tells the story of the “Skywoman Falling” to the students. The teacher is encouraged to tell the story instead of reading, encouraging students to pay attention to the intonation. T to refer to the Teacher’s Guide at the beginning for storytelling. |

| After listening | To show understanding |

|

| Reading | To comprehend the story and learn new vocabulary. |

|

| Speaking | Discussion questions |

Ss to discuss the questions in pairs, followed by WCFB. |

| Freer Task - Speaking | Telling a creation story | Referring to the story map Ss had created earlier, T asks the Ss to create a story map of the creation story from their own culture. Give Ss time to prepare. Ss in pairs now tell the story to each other. Encourage students to use the vocabulary they learnt from the story “Skywoman.” The activity could be done in groups of 3-4 as well, depending upon time. |

| Feedback | Reflection |

T to elicit the values Ss learnt from the story.

T to elicit new vocabulary the Ss learnt. What did the Ss learn about storytelling? How did they feel after sharing stories from their own culture? |

Lesson 2 - Creation Story from the Sts’ailes Nation

| Lesson Stages | Objective | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Lead in | To reflect on the nature of relationship humans share with the natural world. |

Ss are seated in the Talking circle again. Ask students to share their understanding of the interactions between humans and more-than human beings. They can think of both positive and negative interactions based on their cultural understanding and experiences. Encourage them to think on their personal experiences.

Note: T might across complex areas like pet animals, domesticated animals and animals in zoos. All these forms do reflect on the nature of humans keeping animals captive either for entertainment, emotional support, food etc. |

| Reading | To understand the story. To practice reading and pronunciation skills. |

T to handout copies of the story.

Read the text aloud with Ss taking turns. Discuss the central themes of the story - the origin of the world, the evolution of life, the interdependence of all living things, and the responsibilities humans have towards nature. |

| After reading task | To show understanding through art. |

|

| Speaking | To explain the art to the class. | Ss in groups explain their visual representation of the story. |

| Feedback | Reflection | Encourage ss to think and share on how the teachings in the text can be applied in modern life. T to help with language where necessary. |

UNIT 2 - Where does our food come from?

Rationale

Globalization has led to the easy movement of commodities across the world. Human beings as consumers find things from remote corners of the world in supermarkets with relative ease. This unit allows the Ss to reflect on where and how the food they eat come to them. As Harrod (2000) says, “in urban centers, many generations of children have matured into adulthood without any primary experience of domestic animals and no practical knowledge of where food products such as milk or eggs originate” (p.xxiv). This unit also challenges Western cultural assumptions of animals as resources. The Indigenous oral traditions “are rich with examples of how animals gave their bodies to the people, often agreeing to become food because they have established kinship relations with humans” (Harrod, 2000, p. xii). These stories often show that animals are beings with agency and not passive receivers of human’s action

Level: Upper intermediate

Number of students: 15

Total duration: 90 mins + 90 mins

#1 The Bitter Reality of the Bitter Brew

#2 “How food was given captikʷɬ” - The Four Food Chiefs - This oral history is borrowed from Syilx Okanagan People residing in the Southern Interior of British Columbia. It tells the story of how food was given to the Okanagan nation.

Objectives:

-

By the end of the lesson, students reflect on the food culture that is influenced by the modern world and its contribution to environmental damage.

-

Understand the values of sacrifice, generosity, responsibility and community.

-

Be able to reflect on the relationship between humans and more-than-human beings.

-

Be able to critically analyse the root metaphors of nature-centred cultures and industrial cultures.

Lesson 1 - The Bitter reality of the bitter brew

| Lesson Stage | Objective | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Lead in | To activate schemata |

Whole class discussion

|

| Reading | To enhance reading and comprehension skills. |

Jigsaw reading activity (4 paragraphs)

T to monitor the discussions and assist students as needed. How to conduct the activity

|

```

| Language focus | To pay attention to linking words and phrases. | T to elicit from Ss, what did they learn about coffee farming. This is to be followed by feedback on the correct sequence of the text. Elicit from Ss what helped them to identify the sequence. Highlight the linking words/phrases. Elicit a few more options. |

| Final Task - Speaking | To research and present on the source of food items Ss consume. |

|

| Feedback | Reflection |

T elicits from Ss what did they learn from this activity. Is it important to think about where does our food come from?

T could also give language feedback in the form of error correction. |

Lesson 2 - "How food was given captikʷɬ” - The Four Food Chiefs

This story is borrowed from the Syilx Okanagan People who reside in both Canada and the United States.

| Lesson Stage | Objective | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Lead In | To think about the key themes of the story. |

Ss sit in the talking circle. Introduce the concept of a "talking

piece" which will be passed around to ensure everyone has a chance to

speak and be heard. A small token (like a feather, stone, or leaf) to

represent the talking piece.

T to start the sharing circle by holding the talking piece and sharing something they are grateful for in their life. E.g. "I am grateful for the trees that give us air to breathe." Pass the talking piece around the circle, allowing each student to share something they are grateful for. Encourage them to think about things that come from nature (animals, plants, water, etc.). |

| Listening | To activate listening skills. | Ss continue to sit in the circle. T tells the story of the “Four Food Chiefs” to the students. It is important to share where the story comes from. T to use the right intonation, and stress to model a good example of storytelling and to engage the students. |

| After Listening | To check comprehension |

T asks simple comprehension questions to check students understanding

of the story.

E.g. Why do more-than-human beings come together? Who are the four food chiefs? |

| Speaking | To extend Ss understanding of the key values in the story. |

In pairs/group

|

| Reading | To gain a deeper understanding of how the story is connected to the Syilx Okanagan People. |

T to provide handout of the story. Ss read the story silently and

complete the table in pairs. An example has been given.

Instruction for T - The students at this stage, might not comprehend the values as they come from Okanagan Nation. Ss at this stage could offer their understanding. Encourage them to share their cultural connection/meanings with these plants and animals, if any. T to provide details during the feedback stage. |

| Speaking | To engage students in a discussion that deepens their understanding of the themes in the story and enhances their speaking skills. |

Index cards with the questions written on them. Divide the students

into pairs.

Give each pair an index card with one of the three questions:

Facilitate a class discussion based on the pairs' presentation of ideas. Use follow-up questions to deepen the discussion:

|

| Feedback | Reflection | Elicit from Ss the importance of collaboration, respect for nature, and the wisdom we can gain from traditional stories. Encourage students to consider how they can apply the lessons from the story in their own lives and communities. Encourage students to think about how they can incorporate gratitude and respect into their daily lives, not just for people, but for nature and all the gifts it provides. |

UNIT 3 - Relationship between People and Land

Rationale

In today's globalized and modern context, land is often seen merely as property or a commodity. The evolution of urban development has further distanced people from their connection to the land. However, land is far more than a physical asset; it is intrinsically linked to the concept of Mother Earth and serves as the foundation of all we need. This unit draws on the perspectives of Styres et al. (2013), emphasizing that land encompasses water, earth, and air, and is viewed as a dynamic and spiritual entity that extends beyond physical boundaries. It is an essential component of human and cultural identity.

The influence of Western globalized practices has spread across many countries, prompting people to move in search of better employment opportunities. This quest for an improved lifestyle often results in a sense of rootlessness. Through this unit, students will have the opportunity to reconnect with the landscapes of their birth or childhood, fostering a deeper understanding and appreciation of their origins.

Level: Upper intermediate

Number of students: 15

Total duration: 90 mins + 90 mins

#1 Stories in the landscape - The concept of story blanket has inspired this lesson. The story blanket has been generously shared by the Sts’ailes Nation in British Colombia, Canada.

#2 Human-landscape

Lesson objectives:

-

By the end of the lesson, Ss will broaden their understanding of the term

land.

-

Understand the connection between humans, cultures and the natural

environment.

- Be able to use nature-centred vocabulary.

Lesson 1 - Stories in the landscape

Image credit - ‘Story Blanket’ created by Siyam Matilda Charlie displayed at Sts’ailes Band Office.

Photograph by Urbashi Raha, 2024.

Kindly do not reproduce the image without the consent of the Sts’ailes Nation.

| Lesson Stage | Objective | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Lead In | To understand the concept of land. | T writes land in the middle of the board/ mind map software and invites students to write words/phrases they associate with the meaning of land. |

| Speaking | To explore the land Ss are from. |

Ss in pairs discuss:

Where are you from? What do you know about the place? What do you know about the land? Make a list of plants that you know in your area or in general. Which of them are used for food or medicinal purposes? Which animals or plants are native to the land where you are from? What do you know about them? |

| Vocabulary | To help students articulate the geographical features of a land. |

|

| Writing | To help students describe the land they are from. | Using the above definition as an example - Ss are asked to write a description of the land from where they are from. T to walk around and help with sentence structure and other language related errors. |

| Speaking | To create comprehension questions. |

Show the picture and ask ss to frame discussion questions to

understand the image. Pic given in Teacher resource,

E.g. What do they think it is? What does it show? What do the blue-dotted lines represent? What significance could it have for the Sts’ailes nation? T elicits the questions and writes on the board. Giving language feedback as necessary. Ss in pairs now brainstorm ideas and answer these discussion questions. T elicits response from the Ss and provides the answers as a whole class discussion. |

| Vocabulary | To generate land-based/nature-based vocabulary. |

This activity will generate vocabulary related to nature and cultural

understandings of nature. Some of the phrases might seem simple but

the collocation is significant to explain how nature and people are

related.

T should make a note of the words on the board for Ss to take notes as this would be required for a later activity. |

| Task | To create a cultural and ecological map. |

|

| Speaking | To share the maps. | Ss are invited to join the talking circle to show their cultural and ecological maps to other students. They should first read the description they had written earlier, followed by description of the map. The students would be encouraged to use the vocabulary they learnt from the previous activity. |

| Feedback | Reflect | What values did they learn from the story blanket created by the Sts’ailes nation? How did creating the map help the ss to build a relationship with the land they live on? |

Lesson 2 - Human-landscape

This lesson is adapted from the research work done by Dr Chelsey Geralda Armstrong who is a faculty at Simon Fraser University. She is a historical ecologist and ethnoecologist, and teaches Indigenous Studies course at the university.

Please refer to her blog Armstrong (n.d.) “Historical Ecology of Ancient Forest Gardens.”

The listening task resource has been borrowed from the University of California.

Video titled : “The overlooked solution to deadly wildfires in California”

Fig.1 by University of California, (2022)

Watch the video

Image credit - Periphery forest vs Indigenous Forest Gardens by C.G. Armstrong, Reprinted with permission. Please do not use the image for other than educational purposes.

| Lesson Stage | Objective | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Lead In | To activate schemata, to elicit vocabulary. |

T shows two pictures on the screen and asks the Ss to share about what

they notice about the pictures.

Students might point out the different looking trees- the size, the shape, lack of thick vegetation, etc. T to share these are from the British Colombia region. |

| Pre-reading | To generate ideas. |

T to elicit what are forest gardens - food systems that are planted in

a forest.

Students discuss: what might be the ecological benefits of forest gardens? T elicits a few responses and then gives the text on Forests gardens. |

| Reading, Listening and Vocabulary | To learn about the practice of Indigenous forest gardens. |

T to create 3 stations.

Divide the class in 3 groups. T to provide access to Kahoot learning activity in station 1, print out of reading text in station 2 and the video link in station 3. Allow Ss independent learning time at each station. Encourage Ss to take notes of key ideas/words and discuss within their groups as they walk from one station to the other. Station 1 - Vocabulary Station 2 - Reading Station 3 - Listening |

| Speaking | To enhance comprehension and think critically of the benefits of forest gardens. |

Discussion in talking circle. Referring to the blog post and video, T

to generate critical thinking. Encourage Ss to use new vocabulary

learnt as they share their understanding.

|

| Feedback | Reflect |

T to elicit from Ss - What lessons can we learn from these practices

to apply to modern agriculture or conservation?

How can humans contribute positively towards the health of the overall ecosystem? |

UNIT 4 - Responsible Stewardship

Rationale

This unit serves to deepen students' understanding of Indigenous cultures, their values, and their connection to the land and the natural world. By exploring the narratives presented in these lessons, students gain an insight of the symbiotic relationship Indigenous communities maintain with their environment. These lessons are designed to foster appreciation for cultural heritage, teach the importance of community, and environmental stewardship. Additionally, they emphasize the significance of traditional knowledge and practices in maintaining ecological balance and cultural continuity.

Objectives:

-

To appreciate how Indigenous stories and practices convey important values and teachings.

-

To analyze how traditional practices can inform modern sustainable practices and environmental stewardship.

-

To deepen the concept of interconnectedness between human activities and the natural world.

-

To enhance listening skills in order to follow the narratives.

Level: Upper intermediate

Number of students: 15

Total duration: 90 mins + 90 mins

#1 Story of Cedar - Narrated by Herb Rice.

This story is borrowed from the Cowichan Coast Salish Nation from British Colombia, Canada.

#2 Do you like fish?

Lesson 1 - Story of cedar

| Lesson Stage | Objective | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Lead In | To activate senses. |

Ss to be seated in Talking circle.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=95rPwCDHOCE

Play the first 45 secs of the video. Tell the Ss to close their eyes as they listen to the sounds. Pause the video

|

| Before listening | To prepare Ss to listen for specific purpose. |

Before listening provide the students with the discussion questions.

T to clarify terms - transformation, ancestors, ancestral heritage. |

| Listening | To improve listening skills. | Tell the Ss that they are going to listen to the story of the Cedar narrated by Herb Rice. T to also share details of the Indigenous nation. Video to be paused at 5:20 mins. T could play the video in chunks. The students should not be writing answers to the questions as they listen. They can only take note of keywords to help in remembering the story. The objective is to improve students listening skills organically, rather than focusing on the written word. |

| After listening | To discuss key themes and provide feedback. | Ss discuss the questions in the sharing circles. The talking stick could be used for the discussion (a natural object to be used). T finishes with whole class feedback discussing the story with the students, focusing on the discussion questions, themes of community, giving, and the importance of the Cedar tree. |

| Task | To connect with the cultural significance of the Cedar tree and understand the value of community and reciprocity. |

|

| Speaking | To share their artwork and how it represents the themes of the story. | Ss share their work with each other sitting in the sharing circle, highlighting the themes of community and reciprocity. |

| Feedback | Reflect |

T to create a classroom display with the Ss artwork.

T to elicit how did this activity help them to connect with a natural element that might be culturally significant for the Ss community. Share how they can apply the concept of giving back in their own lives. Language feedback as needed. |

Lesson 2 - Do you like fish?

This lesson has been borrowed from the Okanagan-Syilx Nation.

| Lesson Stage | Objective | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Lead In | To activate schemata |

Whole class or pair discussion

|

| Vocabulary | To learn about fishing methods. |

T to divide the class in groups. Each group to be given 2-3 terms

related to different fishing methods. Give some time to research.

|

| Speaking | To present the findings. | Ss present to the whole class on the fishing methods allocated to them. |

| Reading | To learn about the Sylix- Okanagan fishing practice. | Ss complete a gap-fill text as they read. |

| Listening | To learn about the fishing practice of Sts’ailes First Nations community. |

T should then move onto the listening text. This is an example of an

authentic listening text. This conversation was recorded in the

Sts’ailes field school organized by Simon Fraser University. Listen to

this class lecture between Morgan, the professor, Samantha, the

fisheries habitat biologist, and a student about salmon fishing in the

Sts’ailes community.

1st listening - Let the students listen to the conversation. After the listening, ask students what were some of the key things discussed. 2nd listening - Give Ss the transcript. Ask Ss to highlight features of conversational English as they listen. Ss should also underline words they couldn’t understand in the first listening. This should be followed by a brief feedback. T to share - The video was shot in the Sts’ailes community. They can see an example of a modern fish weir and a slough. |

| Writing |

To enhance comprehension and critical thinking skills.

To enhance question making skills. |

Students generate their own questions for this task.

|

| Speaking | To ask and answer questions and discuss important issues. |

Task - Interview

Divide the class in pairs. Student A - To interview student B - on the

text on Okanagan-Syilx people and their fishing practice. Student B -

To interview student A on the listening text on salmon spawning and

sloughs at the Sts’ailes Nation.

|

| Feedback | Reflect |

Ask Ss to reflect on how the Indigenous communities have been good

stewards of the land.

What things can the students do on a daily basis to be responsible to the land? Discuss how did the process of creating questions helped them in better understanding the text. Language feedback. |

Teachers Resources

Unit 1

Skywoman Falling

This story has been adapted from Dr Robin Wall Kimmerer’s book Braiding Sweetgrass. She is a botanist and a decorated professor from the Citizen Potawatomi Nation in Oklahoma, USA.

She fell like a maple seed, spinning on an autumn breeze. A column of light streamed from a hole in the Skyworld, marking her path where only darkness had been before. It took her a long time to fall. In fear, or maybe hope, she clutched a bundle tightly in her hand.

Hurtling downward, she saw only dark water below. But in that emptiness there were many eyes gazing up at the sudden shaft of light. They saw there a small object, a mere dust mote in the beam. As it grew closer, they could see that it was a woman, arms outstretched, long black hair billowing behind as she spiraled toward them.

The geese nodded at one another and rose together from the water in a wave of goose music. She felt the beat of their wings as they flew beneath to break her fall. Far from the only home she’d ever known, she caught her breath at the warm embrace of soft feathers as they gently carried her downward. And so it began.

The geese could not hold the woman above the water for much longer, so they called a council to decide what to do. Resting on their wings, she saw them all gather: loons, otters, swans, beavers, fish of all kinds. A great turtle floated in their midst and offered his back for her to rest upon. Gratefully, she stepped from the goose wings onto the dome of his shell. The others understood that she needed land for her home and discussed how they might serve her need. The deep divers among them had heard of mud at the bottom of the water and agreed to go find some.

Loon dove first, but the distance was too far and after a long while he surfaced with nothing to show for his efforts. One by one, the other animals offered to help—Otter, Beaver, Sturgeon—but the depth, the darkness, and the pressures were too great for even the strongest of swimmers. They returned gasping for air with their heads ringing. Some did not return at all. Soon only little Muskrat was left, the weakest diver of all. He volunteered to go while the others looked on doubt- fully. His small legs flailed as he worked his way downward and he was gone a very long time.

They waited and waited for him to return, fearing the worst for their relative, and, before long, a stream of bubbles rose with the small, limp body of the muskrat. He had given his life to aid this helpless human. But then the others noticed that his paw was tightly clenched and, when they opened it, there was a small handful of mud. Turtle said, “Here, put it on my back and I will hold it.”

Skywoman bent and spread the mud with her hands across the shell of the turtle. Moved by the extraordinary gifts of the animals, she sang in thanksgiving and then began to dance, her feet caressing the earth. The land grew and grew as she danced her thanks, from the dab of mud on Turtle’s back until the whole earth was made. Not by Skywoman alone, but from the alchemy of all the animals’ gifts coupled with her deep gratitude. Together they formed what we know today as Turtle Island, our home.

Like any good guest, Skywoman had not come empty-handed. The bundle was still clutched in her hand. When she toppled from the hole in the Skyworld she had reached out to grab onto the Tree of Life that grew there. In her grasp were branches—fruits and seeds of all kinds of plants. These she scattered onto the new ground and carefully tended each one until the world turned from brown to green.

Sunlight streamed through the hole from the Skyworld, allowing the seeds to flourish. Wild grasses, flowers, trees, and medicines spread everywhere. And now that the animals, too, had plenty to eat, many came to live with her on Turtle Island.

(Kimmerer, 2013, p. 3-5)

Discussion questions guide

1. What values does the story remind us of?

There is no right answer. However, T should look for understanding of values of community, relationship, generosity and sacrifice.

2. Why did the animals sacrifice themselves for a human?

- Ss might find it difficult to answer this question due to influence of modern Western understanding of the relationship between humans and animals. In many Indigenous communities animals are considered kin who sacrifice themselves to sustain humans. There is sense of responsibility that flows between humans and the Earth. We are all part of one ecosystem.

3. What do you think of the Skywoman’s gesture of the gift bundle?

Reflecting on values of reciprocity and responsibility.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————

Lesson 2

Creation story

As told by Chief William Charlie

Sts’ailes Nation from British Colombia, Canada

Before the world was here, the sun and the moon, they fell in love. They said their emotions and their feelings towards each other. Where those feelings met was where the world was created. And at the beginning, that world was covered with water. And it was only through time and evolution that land formed.

And all living things were a result of the sun and the moon. Some took different shapes and different forms. Some became the winged, some became the four-legged fur-bearing, some became the plant people and the root people, some became the ones that swim in the river and the ocean, and some became human.

But our story says that early in time, as humans, we needed the most support to survive. And it was all our relations that took pity on us, and they gave themselves to us -- for food, shelter, clothing, utensils, and medicine. The only thing they asked in return was to be respected, to be remembered, to only take what you need, and to share with those that are less fortunate.

So, all of our practices point back to that. All our ways of harvesting, grooming, looking after, taking, or giving back point back to that story. That's how we are supposed to look after all our relations.

We say we don't own the land; we are the land. For 1000s of years, everything that we are, comes from the land. And when we die, we go back to the land. We are this land. All of our snowoyelh, all of our laws, and all of our s’í:wes, all of our teachings, point back to this story. All of our social laws point back to the story.

Note: The story has been reproduced with the consent of the Sts’ailes nation. Kindly do not use for commercial purposes. Do not publish without the nation’s consent.

T could refer to this website First Peoples Cultural Council & First Peoples Cultural Foundation (FPCC & FPCF, n.d.)

https://www.firstvoices.com/halqemeylem

for the pronunciation of the Halqemeylem words.

Understanding the stories

The Indigenous stories are shaped by the values of respect, kinship and reciprocal nature towards the natural world as a whole. Animals play an integral part in the survival of the human species.

Creation story

As told by Chief William Charlie

Sts’ailes Nation from British Colombia, Canada

Unit 2

Lesson 1 - Bitter Reality of the bitter brew

This article has been compiled by referring to two different sources. Key words have been underlined. T could provide a list of keywords and meanings so that the focus of the activity remains on comprehension, critical thinking and language production.

Handout

Bitter Reality of the bitter brew

Exploitative coffee production leads to massive deforestation

. There are two types of coffee plants, those that grow in sun and those that grow in shade.

Shade-grown coffee is better for the environment in many ways. It prevents soil erosion and provides a home for native species of plants and animals of the regions where coffee grows. The plants used for shade can also give farmers extra income. By preventing soil erosion, shade-grown coffee reduces run-off from agricultural chemicals and uses less water.

On the other hand, sun-grown coffee is planted by clearing forests. It leads to greater loss of rainforest and soil nutrient depletion. As sun-grown coffee plants produce nearly three times as much coffee as shade-grown plants, coffee roasting companies increase production of sun-grown crops. In the 1950s, 15% of the earth was covered by rainforest, but today it's only 6%. This remaining rainforest could disappear in 40 years because over 200,000 acres are burned each day for farming and industry. Sun-grown coffee also needs more chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and fungicides, making it one of the most sprayed crops. Moreover, these chemicals harm workers' health.

Additionally, deforestation decreases the biodiversity of wildlife and plants. These cleared habitats become unsuitable for most species, with only a few able to survive the harmful changes. When forests are lost, the air becomes drier, and the soil and plants change.

Burning forests and tilling the land for agriculture changes the temperature and soil chemistry. Without the forest canopy, the soil is exposed to the sun, losing moisture and becoming warmer and drier. This disrupts the balance of soil organisms like termites, nematodes, earthworms, bacteria, and fungi. Lastly, the new agricultural system that replaces the rainforest can't support the same mix of plants and organisms, causing further environmental harm.

Apart from habitat loss, another concern with the coffee trade is the practice of feeding coffee beans to animals and then using the excreted beans for consumption. Kopi luwak, for example, is a type of Indonesian coffee produced by feeding coffee beans to the Asian palm civet, a small mammal found in the jungles of Asia. It is the most expensive coffee in the world, selling for hundreds of dollars per pound. A single cup can cost up to US$80. Coffee producers claim the civet’s digestion process improves the beans’ flavor.

The popularity of “civet coffee” has led to intensive farming of the animals, who are confined in cages and force-fed the beans. It has been documented that many of the civets in the coffee industry have no access to clean drinking water, no ability to interact with other civets, and live in urine- and feces-soaked cages. Many are forced to stand, sleep, and sit on wire floors, which “causes sores and abrasions.” “It is a constant, intense source of pain and discomfort.” Civets pay a high price for luxury coffee.

A similar process is used in the practice of feeding coffee beans to elephants. Sadly, it’s being carried out at a “sanctuary” in Thailand, where about 27 elephants consume beans from nearby plantations.

Finally, water pollution occurs due to waste-dumping and fertilizer run-off into water sources. Coffee produces an enormous amount of waste, “fifty-seven percent of the coffee bean is made up of contaminants which, when discarded destroy marine life in rivers and streams and harm people.”

Coffee harvesting starts by separating the usable coffee bean from its surrounding pulp. A coffee cherry has outer layers and an inner coffee bean. These are soaked and fermented, breaking down the bean coating and leaving a slimy residue. This leftover organic matter is dumped into rivers and streams, where its decomposition uses up oxygen and kills aquatic species.

While some governments have anti-dumping laws, these laws are not well enforced. Heavy pesticide use for coffee production also contributes to pollution. In 2005, 5 million tons of pesticides were applied to crops worldwide. Pesticide use will only increase as pests become more tolerant to chemicals. Aquatic ecosystems will keep being harmed by water pollution from soil contamination, coffee byproduct disposal, and pesticide runoff.

Source: Varcho (2015) & Food Empowerment Project (2024)

Lesson 2 - The Four Food Chiefs

Context

Kul’nchut’n, the creator visited the Tmixw, more-than-human beings i.e. the animals, plants, air, water. Kul’nchut’n sent Senklip, the coyote to prepare for the future of the Stelsqilxw, people-to-be.

Note: The nsyilxcən language is spoken by the Okanagan Syilx people. Please refer to the Sylix online dictionary for the correct pronunciation of nsyilxcən words https://www.firstvoices.com/syilx (FPCC & FPCF, n.d.).

How food was given captikʷɬ - The Four Food Chiefs

All creation was talking about the coming changes to their world. They had been told that soon a new kind of people would be living on this earth. Even they, the Animals and Plant People, would be changed. They had to decide how the People-To-Be would live and what they would eat. The Four Chiefs were: skəmxist (Bear), n’tyxtix (Salmon), spitlem (Bitterroot) and siyaʔ (Saskatoon). They held many meetings and talked for a long time about what the People-To-Be would need to live. All of the Chiefs thought and thought. “What can we give to the People-To-Be to eat that is already here on earth? There seems to be no answer.”

Finally, the three other Chiefs said to skəmxist, “You are the wisest and the oldest among us. You tell us what you are going to do.” skəmxist said, “Since you have all placed your trust in me, I will have to do the best I can.” He thought for a long time and finally he said, “I will give myself, and all the animals that I am Chief over, to be food for the People-To-Be.” Then he said to n’tyxtix, “What will you do?” n’tyxtix answered, “You are indeed the wisest among us. I will also give myself and all the things that live in the water as food for the People-To-Be.” spitlem, what was Chief of All-the-Roots-Under-the-Ground said, “I will do the same.” Siyaʔ was last. He said, “I will do the same.” All the good things that grow above the ground will be the food for the People-To-Be.

Chief skəmxist was happy because there would be enough food for the People-To-Be. He said, “Now I will lay my life down to make these things happen.” Because he was the greatest Chief and had given his life, all of the People-That-Were (the Animal People) gathered and sang songs to bring him back to life. That was how they helped heal each other in that world. They all took turns singing, but skəmxist did not come back to life. Finally, Fly came along. He sang, “You laid your body down. You laid your life down.” His song was powerful. skəmxist came back to life. Then Fly told the Four Chiefs, “When the People-To-Be are here and they take your body for food, they will sing this song. They will cry their thanks with this song.” Then skəmxist spoke for all the Chiefs. “From now on when the People-To-Be come, everything will have its own song. The People-To-Be will use these songs to help each other as you have helped me.”

That is how food was given to our People. That is how songs were given to our People. That is how giving and helping one another was and still is taught to our People. That is why we must respect even the smallest, weakest persons for what they can contribute. That is why we give thanks and honour to what is given to us.

Note: This oral history (or captikʷɬ) of the Syilx Okanagan Nation is an adaptation of this story and is intended for educational purposes only. No part of the text may be translated, modified, or used for commercial purposes or used in a publication without the express written permission of the Okanagan Nation Alliance.

(Okanagan Nation Alliance, 2024)

Handout for students

| Food Chiefs | What do they represent? | What values they might represent? |

| Chief skəmxist - Black Bear | Chief of all 4 legged animals | The Black Bear represents the traditions and cultural practices that guide our future. It shows respect for elders and teaches us values like sacrifice, generosity, and responsibility. |

| Chief siya - | ||

| Chief n’tyxtix - | ||

| Chief spitlem - |

Answer key for teachers

The story illustrates how the four food chiefs came together as a community to solve a problem. They make important decisions to take care of future generations and their overall well-being. The story is pertinent in understanding the form of governance of the Okanagan nation. To meet the lesson objectives, the values have been adapted from within the cultural framework of the Okanagan nation. It is also an example of how stories can have multiple meanings. For a deeper understanding of how Okanagan nation values described in the lesson, please refer to this link (Simon Fraser University, n.d.).

| Food Chiefs | What do they represent? | What values they might represent? |

| Chief skəmxist - Black Bear | Chief of all 4 legged animals | The Black Bear represents the traditions and cultural practices that guide our future. It shows respect for elders and teaches us values like sacrifice, generosity, and responsibility. |

| Chief siya? - Saskatoon Berry | Chief of all things growing above land | The Saskatoon Berry stands for creativity, innovation, and youth. It shows the importance of respecting young people and solving problems creatively by listening to other’s opinions. |

| Chief n’tyxtix - Spring Salmon | Chief of all that is in water | The Spring Salmon represents preparedness for action. It teaches us to act responsibly with other beings and consider how our actions can affect others. |

| Chief spitlem - Bitterroot | Chief of all Roots | The bitterroot represents the connection between people, animals, land, air, and water. It shows the harmony needed between human and non-human beings for a sustainable world. It also teaches us to value things we can't see, not just the things we can see. |

Answer key : Discussion questions -

How do the 4 chiefs ensure a balanced nutrient rich food source for human beings?

This is related to the food properties of each of the food sources.

How does this story broaden your understanding of the relationship between land, water, more-than-humans and humans?

The story talks about the interdependence of species. Human beings were the last to be created according to many creation stories around the world, and are hence the weakest and needed help from other species for their sustenance. The concept of interdependence also highlights a sense of identity and responsibility associated with the environment we live in. “There is also no privileging of humans as unique in having agency or intelligence, so one’s identity and caretaking responsibility as a human includes the philosophy that nonhumans have their own agency, spirituality, knowledge, and intelligence” (White, 2018, p.127).

Notice how the four chiefs interacted with the each other to solve a problem. What does this tell us?

The problem was solved by consulting four chiefs, not one. It highlights the power of community and collective thinking, challenging notions of individualism.

Unit 3

Lesson 1 - Stories in the landscape

This is an image of the story blanket woven by Siyam Matilda Charlie displayed at the Sts’ailes Band office. It signifies the importance of the stories of the land and their connection to the Sts’ailes community. The story blanket represents places of cultural and geographical importance to the Sts’ailes community.

This is one example of creative visualization of how a map can be drawn. Siyam Matilda Charlie is the knowledge holder of traditional plants and medicines. She has created a traditional

In Halq'eméylem language, Siyam means an elder who possess intricate knowledge of something. E.g. fishing, hunting, or medicinal plants.

This is one example of creative visualization of how a map can be drawn. Siyam Matilda Charlie is the knowledge holder of traditional plants and medicines. She has created a traditional plant wheel of the plants that are found the in Harrison area in different seasons.

Example of vocabulary that might be generated from the activity.

- river flows

- Water landscape

- Wholeness and balance

- Prayers and ceremonies

- Philosophy of something

- Cultural significance

- Representative of something

Resonates something - E.g. resonates the beating of the heart ( this a a good example of metaphorical use of language and goes beyond the concept of metaphor as a structure usually taught in English language lessons).

Explanation of the map for the teachers. Please note only specific weaves have been chosen as per lesson objectives. The explanation has been provided till 3:47 timestamp in the video. Please refer to the video link for further guidance as necessary - Story Blanket Explanation

In this video, Chief William Charlie from the Sts’ailes First Nations, British Colombia explains the significance of the story blanket (personal communication, May 2024). Kindly note that the video cannot be shared without the express consent of the Sts’ailes nation. This video was recorded with permission by Urbashi Raha.

a. The red dots represent places of cultural significance, such as sites of petroglyphs and traditional oral stories.

b. The blue dotted line represents the river that flows through the Sts’ailes territory—the Sts’ailes River and the Harrison River—emphasizing the cultural significance of the Sts’ailes as river people.

c. The yellow circle represents drums. Sts’ailes peoples are powerful singers which is accompanied by the beating of the drums. The drums are usually circular which is representative of wholeness and balance. The beating of the drums itself resonate the beating of the heart. As an important cultural musical instrument, drums are part of prayers and ceremonies. They are made by stretching deer skin, reflecting the philosophy of using the whole animal and not wasting any part of it, since the animal sacrificed itself for humans.

d. The brown figure in the middle is a Sasq’uet, or Sasquatch in English. These supernatural beings protect the forests from harmful activities and are an important figure in Sts’ailes culture. They can transcend between the spiritual and physical worlds.

e. The mountain goat in brown at the top left represents the Sts’ailes people who lived up the mountain. It draws a connection to the origin stories of the Sts’ailes nation.

f. The blue and black weave at the bottom left is the fish weir , linked to the Sts’ailes origin story about how the upper and lower Sts’ailes people came together.

g. The mask in red is used for sacred ceremonies.

h. The orange weave at the bottom of the blue diagonal lines represents the salmon, highlighting that the Sts’ailes are river people deeply connected to the water landscape. Salmon is also an important cultural food.

i.)The yellow, red, black, and grey images at the top middle symbolize the four directions and four seasons. This sacred number represents how Sts’ailes people’s activities are seasonal, with harvesting, hunting, and fishing practices linked to the seasons (e.g., spring is for gathering and harvesting, summer for gathering, harvesting, and fishing, and fall for ceremonies).

j.) The coil at the top right is a petroglyph, reminding the Sts’ailes people of the circle of life. One goes through life tightly coiled and then unwinds in death. The petroglyph also connects the physical and spiritual worlds. The Sts’ailes community holds ceremonies to look after their ancestral spirits, who in turn look after the physical world.

Lesson 2 - Human-landscape

Indigenous Forest Gardens

Indigenous Forest Gardens

Note: An example of periphery forests and forests managed by Indigenous peoples. Reprinted from Historical- Ecology Research by from C.G. Armstrong, (n.d.). Retrieved July 5, 2024, from https://www.chelseygeralda.com/blank

. Reprinted with permission.

Please do not use the image for other than educational purposes.

Picture 1 - A forest that has coniferous trees, hemlock or cedar trees. The space in between and the thin tree trunks show logging activities. These trees are fairly young around 60 yrs old.

Picture 2 - This forest has different types of plants and trees. These are forest gardens which have fruit and nut trees, shrubs, herbs, root food crops and medicinal plants. In British Columbia, it is common to find Pacific crabapple, hazelnut, elderberry or cranberry and other varieties of berries.

T should keep pictures handy to help identify how do these trees, berries look like.

a. Reading - Text

This article is a compilation of two articles on Forest Gardens. It has been adapted to meet the requirements of English language learners.

Hamzah (2024) - https://www.landfood.ubc.ca/indigenous-forest-gardens-look-to-expand/

Armstrong (n.d.) - https://www.chelseygeralda.com/blank

Indigenous Forest Gardens

Forest gardens are places where food production and forests grow together, creating a healthy ecosystem. In these gardens, plants for food and medicine grow widely. The land is managed through practices like transplanting, fertilizing, and burning, resulting in forests with hazelnut, Pacific crab apple, berry crops, and root foods and medicines.

Dr. Armstrong’s research shows that, like many Indigenous communities worldwide, Indigenous peoples in the Pacific Northwest increased the growth and productivity of plant foods near their homes. This challenges the idea that Indigenous peoples on the Coast did not manage plants and counters the view that human actions usually cause large-scale species loss. The research shows that forest gardens were managed by transplanting, gardening, burning, and pruning, providing ecosystem services for humans in the past. These gardens still provide important functions today. The increase in large-seeded fruits and animal-pollinated species shows that these places now offer important habitats for animals like bears, deer, and moose, and for pollinators.

This research also recognizes that temperate rainforests in the Pacific Northwest are not wild and untouched. Human practices over thousands of years, along with social institutions and governance, helped shape these multifunctional and biodiverse forests, while supporting food production and ecosystem health.

Armstrong (n.d.) & Hamzah (2024)

b. Video for listening task - Fig.1 by University of California (2022) Watch the video

c. Vocabulary - Link to Kahoot - T should familiarize themselves with the platform. Alternative is to create handouts.

https://create.kahoot.it/share/indigenous-forest-gardens/2a36cba1-f4ee-4aff-8b34-4e99dd4b8e8d

- Ecosystem

- Transplanting

- Burning

- Pruning

- Temperate

- Biodiverse

- Pollinators

Indigenous Forest Gardens